Developers Corner

Ethereum is the world’s decentralized-computer. It is the most intricate blending of computer-science, governance, sociology, and economics. However, it’s scale brings with it huge amounts of complexity. Understanding how it works requires a detailed understanding of data-structures, cryptography, theoretical-computation, and much more. But, when you break things down into their individual parts, it’s not too difficult. Keep reading, and you will discover exactly what makes this machine tick, and how you can get the most out of interacting with it.

Cryptography

Like all cryptocurrencies, Ethereum relies on Public-Key-Cryptography, and Digital Signatures.

Ethereum relies on Elliptic-Curve Cryptography, specifically the Secp256k1 Curve Library. It shares this characteristic with Bitcoin, allowing many of the same library functions to be used.

You start by generating a private-key pair using your favorite encryption library, keeping your private key secret. Your address is the Keccak-256 (SHA-3) Hash of your public key.

An Ethereum private key can be generated using the BIP39 Standard Mnemonic Library.

All transactions require the use of the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) from the private key associated with the address. You sign your transaction with your private-key, and it is verified by the nodes to confirm its authenticity before processing.

When using your private key to sign a message, you must also include a special value: a nonce. This is a scalar value equal to the number of transactions sent from this address or, in the case of accounts with associated code, the number of contract-creations made by this account. Every time you send a transaction this value increases, and is necessary to ensure signatures are unique for each transaction to prevent double-spending.

Smart Contract Code

In Ethereum, a smart contract is written in a custom programming language, known as Solidity (although there are others such as Vyper). By spending ethereum as a transaction fee, you can cause the contract to execute in a pre-determined way. Solidity is turing-complete, statically typed, supports inheritance, libraries, and complex user-defined types among other features.

Take the following code snippet of an example smart contract:

/*version number*/

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

/*contract name*/

contract example_contract {

/*function name with parameters and return values*/

function add(uint256 a, uint256 b) returns (uint256) {

return a + b;

}

}

This is a smart-contract written in Solidity. It’s name is example_contract It contains a single function, called add. This is a function that takes an input of two-numbers and adds them together, returning their sum. When you deploy this contract, it is given its own address, much like your wallet. If you wanted execute this contract, you would initiate a transaction with the contract’s address, and execution information. This information includes the name of the function you are calling, the input values, cryptographic signatures, etc.

Because the contract has a valid address, when deployed it can also do things such as hold balances like a normal wallet. This allows you to do things such as send Ether and various tokens to it to hold, and distribute. However, nobody owns the private key to this address. If you wanted to withdraw from the contract, you would have to write in various functions to allow you to do so. Take this example code.

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract example_contract2 {

uint256 balance = 0;

function send_ether(address payable recipient) payable {

balance += msg.value; /*msg.value is the transaction value*/

recipient.transfer(balance) /*send the balance to the recipient*/

}

}

This code contains a method that allows you to store and send ether from one person to another. If you see the word payable means that if you call this method, you can send ether alongside the input value of a recipient, and the contract will do with it what you specify. If you don’t specify to send it somewhere, then it will hold the amount in its account balance for the contract. This is useful because it allows you to specify what to do if someone sends ether to the contract address, alongside relevant input data. For applications like DeFi, or that involve sending money around, it is a very powerful tool for trust less funds exchanges.

Imagine what you could do when you take this concept and make it more complex.

Contracts are immutable. This means that once a contract is deployed, it CANNOT BE MODIFIED. Certain variables can have values be changed, but code logic cannot. If you deployed and then realized that the contract had a bug, your only choice is to deploy a new contract that fixes this.

Logs

You also have the option to publish the metadata about a transaction, that you define. These logs are known as events. Take the following code.

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

//Declare an Event

event transfer(address indexed _from, address indexed _to, uint _value);

contract example_contract2 {

function send_ether(address payable recipient) payable {

emit transfer(msg.sender, recipient, msg.value);

}

}

We first declare an event and its parameters. In this case it’s transfer and it requires a sender, a recipient, and a value. When the function send is executed, it will publish this metadata to the chain alongside the rest of the transaction, as JSON data. This is done with the keyword emit. We can view this on a block explorer beautified to look like this

Image Source: Etherscan.io

We can see the value of all the inputs. This is a high-level topic but because we used the keyword indexed on the two addresses, the EVM has classified them as topics. This is so that the EVM can more easily classify and reference them later. If we were to not use the indexed keyword, they would be below in the data category, alongside value

The address listed is address of the contract that emitted the log. This is necessary because a contract may invoke a function on another contract, known as an internal transaction. This is still considered part of the main initial transaction for block purposes and is useful to keep track of transaction history.

More detailed information can be found here.

These next 3 sections are going to be more tech-heavy so if you don’t have a CS or tech background, feel free to skip to the next article, as you don’t need to understand it to be able to use Ethereum. Otherwise, I’m still going to try and keep it simple.

Blockchain as a State Machine

State Machines, if you’ve ever read this book, you’re probably breaking out into a cold-sweat right now

Image Source: Michael Siper, Introduction to the theory of computation, 3rd edition

Don’t worry, I’m going to keep it simple. The entire Ethereum network, at any given moment, can be represented as a state. Every time a transaction occurs, the state changes. Therefore we can represent the network as a state machine. The following examples are in the Ethereum Whitepaper.

Think of it like this

APPLY(S,TX) -> S' or ERROR where S = The current State and TX = The transaction value.

In a real-world sense, imagine the following: APPLY({ Alice: $50, Bob: $50 },"send $20 from Alice to Bob") = { Alice: $30, Bob: $70 }. It took the current state of all balances, processed a transaction, and returned the new state.

How this state is calculated is detailed below.

This is important because we then can understand how smart contracts fit into this model. The use of a state machine allow the network to store the current state or values of a contract at any given time. Given as these contracts can have lots of variables to track, this is essential. It also allows us to create many layer-2 scaling operations off-chain. This I will explain later.

More detailed information can be found here.

Accounts

Unlike Bitcoin, Ethereum supports the idea of an account, with a balance. This is how the EVM is able to calculate the current world state, based on the value of all valid-addresses.

“Wait, if Bitcoin doesn’t actually have a balance, how come I can go to a website and it tell me how much Bitcoin I have?”

This is a good question. The answer is that Bitcoin doesn’t actually have the concept of an account balance. When you go to a website, that site specifically has indexed the blockchain on their own and created a local copy that they then serve to you. It looks through your transaction history and calculates how much Bitcoin you have, instead of looking at the chain directly for every query. This would be very slow. Your balance is the sum of all of your previously income transaction values. Each transaction has a BTC value. Imagine you wanted to send 5 BTC. Your wallet takes several transactions from your history, and bundles them together until the sum of their values is >= 5 BTC. It then takes that amount, and sends it, and returns the extra unused Bitcoin to you.

Look at this example transaction

Image Source: Blockchain.com

You can see that the input is multiple transactions until the amount is high enough to send it out to other places. This also means that amount you pay in transaction depends on how many inputs and outputs you need. If you look below you’ll see that transaction fee is measured in sat/Byte. The bytes is the sum of all of the data (measured in bytes) both input and output of a transaction. The more inputs and outputs, the larger the size of the transaction, and therefore cost. Sat is the amount of BTC you are willing to pay for each of those bytes (sat = satoshi = 1e-18 BTC). Obviously this is a bad way of doing things because if you transact in smaller amounts, when you want to make a larger transaction those fees can add up. It’s also just incredibly redundant, and prohibits layer-2 scaling solutions such as rollups and sidechains. This is why the only substantial Bitcoin proposed-scaling-solution is the Lightning Network, a side-channel implementation with its own set of problems. This is a system known as UTXO, Unspent Transaction Output. It means that for every input for a transaction, it must from the specified output of another transaction. This is also how Cardano works.

Ethereum, and a number of other blockchains, use a different system of account databases. In Ethereum, in order for contracts to be able to support the ability to transfer values, it must re-imagine this. I.E you must be able to query the amount of Ether in any address in existence and have a native balance value for each address in existence. This means that when you make a transaction, it is much simpler for the network to send coins around, and simplifies many API’s and operations.

Every node on Ethereum accomplishes this by maintaining a database of all currently utilized Ethereum addresses, and their balances. Remember that all Ethereum addresses are just the SHA-3 of a corresponding public-key. This means that all 2^256 addresses technically exist. When a new address becomes active, by receiving some token/coin, it gets stored in the accounts database. This database is a simple key-value store, where an address has a corresponding value, it’s current balance of Ether.

There are two-kinds of accounts: Externally-Owned-Accounts (EOA), and contract accounts. An EOA is any address/account used by a person normally. It is every account that is not a contract. Contracts are kept separate because in addition to the balance, their code needs to be stored as well.

As you can see, the nonce and balance are the same in both. The Nonce is the incrementing integer representing the number of transactions sent from this address. It’s changing value is necessary to ensure that each digital-signature is unique, and to prevent double spending. Both types also have a balance that must be kept track of.

Contracts however, have two values the EOA does not. The first is the storage hash. This is the hash of all of the variables the contract maintains. For example, a contract may contain a data structure such as a list of arrays, and a variety of integers. This is kept in storage, and the hash updated when the values change. The code hash is the hash of the contract-code itself, and does not change once-created. Because EOA’s do not have code or objects to maintain, they don’t need to hold these values. When you make a transaction to the zero address, you’re telling the network to initiate a special transaction to update the accounts-database with this new account.

This is also what people mean when they express concern about “the ethereum state growing”. It means the accounts database is growing ever larger, as well as the history of the blockchain. This is also what people mean when they talk about stateless ethereum. It means to have a new type of node that stores the world-state, but not the entire accounts database needed to compute it. Stateless Ethereum may be discussed in future articles.

This system does have some drawbacks however. Unlike UTXO, when reading and writing to the accounts database for each transaction, the ordering of transactions within a block matters. This is because the ordering in which contracts interact with the accounts database matters. Otherwise, you end up with concurrency issues. The EVM doesn’t do parallel computation very well as a result, but it does do finality and conflict-resolution. This is what leads to something known as MEV (Miner-Extractable-Value). It is when miners will essentially collude with users to order transactions within a block, in a way that is financially beneficial to themselves. I demonstrated this when talking about Uniswap Front-Running Attacks.

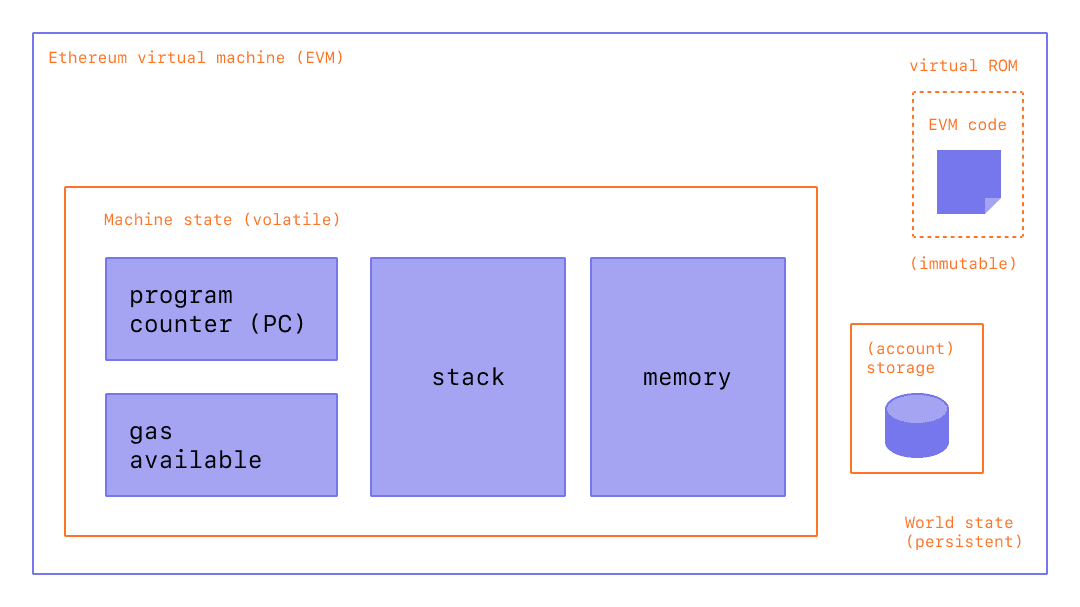

Ethereum Virtual Machine

To calculate the state, we first need to execute a valid transaction. We can do this through The Ethereum Virtual Machine. Think of it like Java. When you write a program to do something, the Java code compiles down to byte-code, which is run through the Java virtual machine. This virtual machine runs on top of your normal Kernel, to make it OS-Agnostic and converts it further to machine code executable by your kernel. The Ethereum Virtual Machine works the same way.

Every time you execute a transaction, the inputs and steps are converted into EVM-Bytecode. The machine takes the current state and performs the transaction and generates a new global-state. When you initially create a new contract, the contract gets converted to bytecode, and stored on the chain with its address. When you make a transaction the proper bytecode is queried and executed. This also explains why contracts are immutable.

The contract address is based on the creator’s address and nonce at the moment of compilation, then hashed. Imagine the following function that gets called every time a contract is created:

def mk_contract_address(sender, nonce):

return sha3(rlp.encode([normalize_address(sender), nonce]))[12:]

You cannot modify a contract, once deploy, because that would require recompiling the contract-bytecode, which is a special transaction. Given that the nonce for an address is incremented with every transaction, you would not be able to recompile the contract-bytecode and deploy it to the same address because the transaction would have a different nonce, and therefore a different address.

The following information is provided by Ethereum Website:

“The EVM executes as a stack machine with a depth of 1024 items. Each item is a 256-bit word, which was chosen for the ease of use with 256-bit cryptography (such as Keccak-256 hashes or secp256k1 signatures).”

“During execution, the EVM maintains a transient memory (as a word-addressed byte array), which does not persist between transactions.”

“Contracts, however, do contain a Merkle Patricia storage trie (as a word-addressable word array), associated with the account in question and part of the global state.”

“Compiled smart contract bytecode executes as a number of EVM opcodes, which perform standard stack operations like XOR, AND, ADD, SUB, etc. The EVM also implements a number of blockchain-specific stack operations, such as ADDRESS, BALANCE, KECCAK256, BLOCKHASH, etc.”

“All Ethereum clients include an EVM implementation”

Image Source: Ethereum Foundation, ethereum.org

Because the EVM is really just a stack-machine using a series of opcodes. Gas cost is determined by which opcodes you use. Each one has a specific cost. Simple ones like ADD, to add values together, only use 3-gas. More difficult ones like BALANCE, to retrieve an account-balance from the accounts database, use 400-gas. This is why optimization is so important. If you can reduce the number of unnecessary operations in your code, you can save users a lot of gas.

Remember earlier when I said the accounts database stores the smart-contract code. Well what it’s really storing is the EVM-Bytecode, and calling that on transaction request. When you use a tool like Remix IDE, you’re using a solidity-compiler to generate the bytecode, which is stored.

Image Source: Luit Hollander, medium.com/mycrypto

There is also a special opcode known as SELFDESTRUCT. While contract-code can’t be updated, it can be deleted from the network. By calling self-destruct, the contract bytecode and address is deleted from the account database, and the remaining contract balance is sent to the specified address. As a reward for cleaning up the database, the EVM will refund a variable amount of gas to you. This is determined by a formula and current conditions.

It is important to remember, that when a contract is published, it is only publishing the EVM-Compatible-Bytecode, not the source code to the chain. The source code can be published on an explorer such as Etherscan where it can then be checked against the bytecode for accuracy. If you are deploying a contract, this is important so that people know what they are interacting with and how to do so properly.

Trees

I’m sorry, but I need to send you back to sophomore-year data structures class to explain this next part. Don’t worry I’ll do my very best to keep it simple. The EVM calculates the new global state at the end of each transaction, after all the values and variables are done being changed. The world state is the state-root of a modified merkle-patricia tree. I’ll walk you through exactly what that means.

Merkle Trees

Take a binary tree. Normally, you start with the root and work you way down to the leaf-nodes. A merkle tree works the opposite way. You start with the leaf-nodes and work you way recursively up to the root. A merkle-tree is used to verify the integrity of information in transit. Think about it like combining a checksum with a tree.

Image Source: Wikipedia

Let’s say you have a file. Split the file into a series of leaf-nodes, each the same size. Let’s say 256-bits, and order them sequentially. Then take the hash of each leaf-node. That becomes the immediate single-parent. Then take the immediate sibling, block N+1, and concatenate it to block N. Then hash that and it becomes the parent of block N and N+1. Repeat this on the next-2 siblings until you have created an entire generation of parents, and continue the process recursively, until you get to the root. The hash at the root of the tree is the merkle-root.

The point of this data structure is to verify the integrity of files in transit, even if you only have part of the file. This is how torrents work to verify your download. By downloading different parts of the file from different sources, you can verify the integrity of the file at the end as long as you know the order they go in. If you only have half of a file, the same logic applies. You only need the left-side-root of the tree to verify the data-blocks you’ve already received. This allows you to receive different parts of the file at the same time and ensure that they can individually be verified without needing the rest of the file.

The World state of Ethereum is the Merkle-Root of a modified-patricia-tree.

Patricia Tree

A patricia tree (AKA a Radix-Tree) is a type of tree, where each successive generation is used to generate a complete piece of information.

Starting from the root, each child-node appends a new piece of information until you terminate in the leaf-node. The Ethereum patricia-tree uses this concept but with addresses. Take the following diagram. It seems daunting at first, but is more simple than it seems.

In this tree, the leaf-node is a completed address, with its balance, the key-value pair. At each generation in the tree, another nibble (2 characters) get added to the address until completed. The extension nodes are to add nibbles to the address, and the branch nodes then to connect them all to eachother. Using this model, you can construct a tree for every possible address and its value. This is the accounts-tree. Once this tree is constructed, start taking a merkle-root. The merkle-root of this tree, working recursively up the tree, is the state root of the tree.

More information on how this works can be found in the Ethereum Yellow-Paper.

Bytecode, Sourcecode, and ABI

When you compile a contract, the compiler will generate an Contract ABI (Application Binary Interface) This is the standard way for you to properly create transactions by defining the functions and inputs required. If looks similar to JSON. If you publish a contract, you should also publish the ABI alongside it, on a block explorer or somewhere people can find it. Wallet applications will use this information to guide you through the process, compile, and properly encrypt and sign the transaction. Without it, people will have to decompile your bytecode and attempt to figure out how it works. This runs the risk of them sending faulty transactions. Transparency is your friend. Nobody can or will use a contract with faulty source code and no ABI.

An example, compressed for space. It includes all of the decompiled function information your wallet needs to create an EVM-Compatible Transaction:

[{"constant":true,"inputs":[],"name":"name","outputs":[{"name":"","type":"string"}],"payable":false,"stateMutability":"view","type":"function"}

More info on ABI’s can be found in the documentation

Client-Types

There are 4 different types of Clients that can be run on Ethereum:

“Full” Sync - Gets the block headers, the block bodies, and validates every element from genesis block. Contains everything.

Fast Sync - Gets the block headers, the block bodies, and processes no transactions until current block - 64(*). Then it gets a snapshot state and goes like a full synchronization moving forward. It lets you get up to current status very quickly if you don’t care about history.

Light Sync - Gets only the current state. To verify elements, it needs to ask to full (archive) nodes for the corresponding tree leaves to regenerate the entire world-state from the merkle-patricia-tree.

Warp Sync - Built for the OpenEthereum Client, it involves sending snapshots over the network to get the full state at a given block extremely quickly. Then, in the background, it fills in the blocks between the genesis and the snapshot block. It lets you immediately jump to a certain point and then fill in the history behind it which may be less important at that-very-moment. More info can be found on the OpenEthereum Website.

Transaction lifecycle

- What happens when you want to send a transaction. There are several steps:

- Constructing the raw transaction. This is in the form of a signed raw transaction hex. Your wallet constructs the raw transaction data, and signs it with your private key. This contains several fields:

The Nonce, in hex. The unsigned integer that represents your transaction count, to prevent double-spends. It is incremented every time you make a transaction, to prevent replay transactions.

Gas Price, in hex.

Gas Limit, in hex.

the recipient, the “to” field.

the transaction value, in ether, also in hex.

- Extra transaction data. Only necesarry for a smart contract interaction. Calculated automatically by your wallet. If you want to do it yourself though, it’s very easy:

- Take the sha3 of the function signature from the contract ABI, without the parameter names.

If the function signature is

mint(address to), then you should only usemint(address). This is because the EVM doesn’t care about the parameters, it just needs to be able to identify the function.web3.utils.sha3("mint(address)")0x7f9c8b4781db704d0917ecead0efa9e769fadacf34db8e74afcc18c0c8f35497

Take the first 4 bytes of the hash ->

0x7f9c8b47- Take the input parameters, and convert to bytes32, a 32-byte hex string. If the value of the string is less than 32-bytes, pad it on the left. If it is an address, or already in hex form, just do the padding, no extra conversion required.

0xaB5409b0E5a66AcC9D63f668414539A60a5917C1000000000000000000000000aB5409b0E5a66AcC9D63f668414539A60a5917C

Repeat for each input parameter, and append to the function signature.

Sign the transaction with your private key.

Submit your transaction request by sending it to a local node. This means that the transaction construction and signing can be done offline. This is often to protect the secrecy of the security key and prevent transaction tampering. You can do this using Etherscan’s nodes by submitting the raw transaction data.

The node will propagate the unconfirmed transaction to its peers, if they choose they will add it to their mempool. Some may reject it if they feel the gas is too low or if the transaction is invalid. This is because the mempool has a finite size.

The transaction sits in the mempool until a miner chooses to include it in a block. They include it in the block and execute the transactions and mine it until completion.

Nodes propagate the new block and state information through its peers. If the block is accepted, they will add it to their chain. If not, they ignore it.

Propagation continues until the entire network has the updated blocks.

Process repeats indefinitely.

Ethereum Development and Governance

If you’re going to build the world’s largest decentralized computer, you also need a way to change things about it. However, how do you do this without creating another centralization bottleneck. Ethereum therefore has created a distributed development process. There is not one entity responsible for development, but many. The Ethereum Foundation is the non-profit entity for doing 2 things, coordinating updates to the platform, and building 1 type of client.

An ethereum client is simply a program resposible for receiving blocks, creating new ones, and maintaining the network. There are many different versions, built in different languages. For example, there are currently clients built in languages such as Go, Rust, C#, Java, etc. Each one is maintained by a different company. Geth, built in Go, is maintained by the Ethereum foundation, and was the first client-type. The C# client is maintained by Nethermind, a for-profit-company based in England.

The purpose behind this was to make it so that one developer didn’t maintain exclusive control over the protocol, creating centralization risk. By diversifying clients, the security risk goes down because the risk of a chain-breaking bug is localized to a single client-type. It also prevents a company from holding the community hostage over the demands of their clients.

However, this system only works in a world where all of these clients and companies are on the same page. This is where the Ethereum foundation comes into play. The foundation is the entity for coordinating development between the different client maintainers. They are responsible for maintaining the list of things a client needs to be able to do, so that all clients could follow it. Let’s say you wanted to be cool and build a client in brainfuck, besides being a masochist, you would be able to do so. This is because the Ethereum foundation keeps a detailed specification of requirements for each client. If you follow it, and implement it in your language-of-choice, then your client will be able to interact with all others without any problems. If you don’t then you won’t be able to interact properly, and if you’re building a staking client you may even be responsible for users being slashed, and lose their stake.

Client |

Language |

Operating System |

Sync Strategy |

Geth |

Go |

Linux, Windows, macOS |

Fast, Full |

Nethermind |

C# .NET |

Linux, Windows, macOS |

Fast, Full |

Besu |

Java |

Linux, Windows, macOS |

Fast, Full |

Erigon |

Go |

Linux, Windows, macOS |

Fast, Full |

OpenEthereum |

Rust |

Linux, Windows, macOS |

Warp, Full |

EIP’S

EIP, short for Ethereum-Improvement-Proposal is the method by which new ideas are implemented into Ethereum. Let’s say you had an idea for how to make Ethereum better. How would you get it implemented? Well first you need to write down exactly what it is. You specify things like category, motivation, specifications, pros and cons, etc. The exact details of what this looks like can be found here, EIP-1.

Once you’ve written your EIP, you simply submit it to the community and start to build support. It is your responsibility to build support for your proposal. Once it gains enough traction it goes to the Ethereum Core Developers

Ethereum Core Developers

The Ethereum core developers is the group of people most involved in the development of Ethereum. There is no formal delegation or election process, it is simply a group of people the community has designated as important. They are people from the foundation, heads of or engineers from companies most involved with the platform’s development. They are the people most responsible for coming to a consensus on EIP’s that should be improved. Every 2-weeks they all meet on a zoom-call (open to the public) to talk about updates.

They talk about proposals and debate the merits and come to a rough consensus on whether they should be included. If agreed, they go back to their companies, and community and work on individually implementing the EIP into their software. They are given the title of core dev because they are important in making sure things get implemented. For example, the chief engineer at the Ethereum Foundation, and Geth is a core dev, because they will be instrumental in the client’s implementation of new EIP’s. Vitalik, being the head of the foundation, is essential as well. It is not a formal title, that can be given or taken away.

They are not elected, nor hold any more power than anyone else. Before you think they are some shadowy cabal responsible for arbitrarily deciding things, they arne’t. Their status and importance comes from the ability to shepard implementation of approved EIP’s. They are also very public and reputable individuals, who have attained the status through their altruistic contribution history to the community. It can be taken away if you stop contributing to the community. They don’t have any extra power than you and I, they are simply just developers who represent different teams and segments of the community to come to a rough consensus, without the need to complex voting-systems.

This article by Hudson James does a good job explaining it as well.

Forks

Congratulations, your EIP was approved and now needs to be formally implemented into the protocol. How does that happen. With a fork. Since the blockchain is immutable, the only way to change the rules is to keep moving forwards. When an update occurs, so does a fork in the chain.

- There are two types of forks, Hard and Soft:

Soft Fork - A soft-fork means backwards-compatability. Only previously-valid blocks are made invalid. This means that old, un-updated, clients and versions can still interpret new updates without change. For example, a gas cost change. If you wanted to increase the gas cost of an ADD operation from 3 -> 4 gas, then that would be introduced in a soft-fork. This means older clients can still interpret new blocks without upgrade. It is used for upgrades that don’t require a change in consensus rules.

Hard Fork - A hard fork is for a change in the consensus mechanism. When occured, much like the proverbial road-less-travelled, the chain goes in two-different directions. One with the old rules and one with the new rules. You can choose to keep mining or validating blocks on whichever chain you like, with identical histories up until that point. However, once the two chains diverge, they will never reunite. This means picking the chain with the most people on it is the best-option. Take Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash. The two split because of an increase in block-size. Because the two chains have different consensus rules, they are no longer-compatible. Every node must upgrade to the new consensus rules in order to properly validate blocks. EIP-1559 was a hard-fork because it required a change in consensus on the creation/burning of new coins, as well as block size. Most major changes to blockchains utilize the hard-fork.

Image Source: Investopedia